Richard Long never carries water with him when he walks. The legendary British land artist, who famously turned walking into an art form, has tramped for days, sometimes weeks, through terrains as barren as the South African Karoo desert, India’s tribal lands and the Hoggar mountains of southern Algeria without once taking so much as a canteen, a flask or – God forbid – a plastic bottle with him.

“It’s just a question of what’s practical,” he says. “Water is heavy. Finding it is one of the things that determine where I go. When I got to the Sahara it had just rained. I could see it shining on the ground. I followed it till I got to the first dried-up watering hole.”

Now 77, Long is tall and rangy, as you might expect of an inveterate walker, 6ft 4in, with a wayward glint beneath his beetling black eyebrows and an air of slight restlessness, as though he might get up and bound out of the door at any moment.

So I take it the title of his new exhibition, Drinking the Rivers of Dartmoor, isn’t intended metaphorically? “Not metaphorical at all,” he says shortly. “I’ve been drinking from every river and stream on Dartmoor all my adult life.”

The afternoon in 1967 when Long, then a 22-year-old student, decided to walk back and forth across a field until he had created a line of flattened grass, then photograph it and call it A Line Made By Walking is one of the great mythic moments in British art. In one simple gesture, Long set the tone for British conceptual art and initiated an entirely new art form: land art, which in its British form, personified by Long, was more fugitive, less monumental than the American variant – about gestures rather than bombastic structures. Long would go on epic walks and come back with nothing more than a photograph of a ring of stones he’d made on a mountain top or the briefest description of where he’d been. That would be the work.

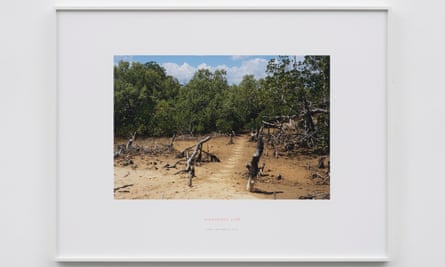

Long has extended that idea into gallery-based art, with elemental circles of shattered slate and wall-filling drawings of smeared mud, winning every major accolade – Turner prize, Venice Biennale, CBE. Yet art conceived and created in the landscape, which deals with time and space, but seems to exist in a permanent present, remains the core of what he does. So it’s interesting, and surprising, to see him looking back in this new exhibition, not just to older work from as far back as 1970, but to recent pieces with a retrospective, even autobiographical feel.

The title work, Drinking the Rivers of Dartmoor, a wall-filling text, is essentially a list of 14 streams (Yealm, Erme, Plym etc), laid out like a piece of concrete poetry – though he stresses such works absolutely aren’t poetry. It’s based on a six-day “ritualised walk around one of my life’s prototype landscapes” – not so far from his home in Bristol – “that I’ve used as a tabula rasa, a blank page, to do whatever I want. Dartmoor has been in a way my studio.

“I now have a lot of history. I feel as though each time I go on a walk I carry the history of all the other walks I’ve done with me in my rucksack. And why would I not?” he adds in a faintly challenging tone.

While I’ve always imagined Long as aloof, ascetic, probably privileged in the classic mode of the British explorer, in person he comes across as very much a bloke from Bristol. There’s an earthiness, despite the air of slight otherworldliness, a sense rare in our increasingly globalised art world – where artists typically work between several major centres – of profound rootedness in the cultural and geographic terrain that shaped his work and worldview.

Born in 1945, the son of a primary school teacher, Long was raised in Clifton and grew up using the towpath along the nearby Avon Gorge as his “playground”. The knowledge that this area has the second highest and lowest tides in the world, which allow Bristol to function as a port, gave him his “first awareness of the cosmic forces that control everything”. While such a realisation feels only natural in an art of time and distance in which planetary and seasonal movements have an essential role, he seems uneasy at this admission, concerned it will make him appear pretentious.

Yet it’s essential to Long’s sense of himself that he has “always been an artist”. His teachers were sufficiently impressed by his abilities to excuse him morning assembly so he had “half an hour’s painting time on my own every day”. That “on my own” feels significant. Long insists he enjoys meeting people, but the path he has taken has always been his own.

While it was clear he would start at Bristol’s Royal West of England Academy at the earliest opportunity, he was soon at loggerheads with his teachers, as his early passion for Van Gogh made way for a form of self-devised installation art. After seeing a floor-based sculpture by the Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi at the Tate, at a time when he was reading Bertrand Russell’s pop-science book The ABC of Relativity, Long made a plaster path through the college studio to “explore relative movement, using the body as a moving object over still things”. This sounds pretty far out for a 17-year-old who by his own admission had “no idea what was going on in art”. But the RWA staff were less than impressed and, after informing his parents that their son was “mad”, promptly expelled him.

Long, however, had no intention of giving up. While his breakthrough work, A Line Made by Walking, tallied with the most advanced developments in global art, you get the sense that Long, left to his own devices, might have arrived at that era-defining conclusion quite independently.

In the freezing winter of 1964, while doing odd jobs for Bristol council, Long went up on to the Downs, the open green space adjoining Clifton, made a snowball and “kept rolling it till it was so heavy it wouldn’t move any more”. He then photographed the dark track through the snow as a “drawing”. “It was,” he says, “the perfect prototype for what I was going to do in the rest of my life: something I did with my own physical effort, using the materials of the place, then recording it in an image to show people what I’d done.”

after newsletter promotion

But was the work deliberate, knowing, or had he just been mucking about with a snowball? He racks his brains. “It must have been deliberate, because I had the camera with me. When you’re a young artist you don’t understand what you’re doing. I just had the feeling of the potential of the world outside the studio.”

Cut to 1967, when as a student on the advanced sculpture course at London’s St Martin’s College, where he was part of a famously experimental year that included Gilbert & George, Long effectively restaged this performed sculpture in the work that was to make him famous.

“I took a suburban train out of Waterloo. As soon as we were in the countryside, I got off at the first station. I found the first field I came to, and I made the line.” This was at the height at the Summer of Love, in a moment when pop art had run its course, and no one in Britain knew where art was going next. “There was all this fantastic music being made, the Beatles, psychedelia. But I was quite proud that what I was doing had nothing to do with that. I knew I was doing something really important – expanding the territory of art.”

Succeeding walks became progressively more ambitious. After creating what he intended as the world’s highest work of art, by leaving a flag at the top of Kilimanjaro, he produced A Thousand Hours, A Thousand Miles in 1974, a spiral walk through central England, including the middle of Birmingham. “In A Line Made By Walking I made a trace on the land, and that was the work. But in this piece there was no trace. The symmetry of the idea was the work. You could say that traditional sculpture was about the space between objects, and here I was extending that into 1,000 miles.”

It’s one of the core ideas of minimalism, with which Long has been closely associated, that art shouldn’t evoke anything but the material actuality of its own form. Yet Long’s art is hugely evocative on many levels. His elemental forms feel familiar to people, whether they’re a cross in a meadow formed by pulling the heads off daisies or a circle of boulders left in a high mountain pass. They seem to echo the primal traces left by ancient cultures: the vast “ground drawings” created by Indigenous Peruvians or Britain’s Neolithic stone monuments.

Long declares himself open to the coincidences that naturally occur between forms and cultures. He’ll even concede there’s a spiritual aspect to his work, though he doesn’t want to talk about it for fear of appearing – again – “pretentious”.

He has always denied, however, that his work has any connection with Wordsworthian English Romanticism. “Not at all, no,” he snaps, with the words barely out of my mouth. But isn’t there also time, distance, seasons and circles in, say, Turner’s paintings? “Of course there is! And I’m a product of England, brought up on an island, going for holidays on the coast, always looking at the ocean.”

Lockdown made him realise how much he could do by walking out of his front door, exploring the labyrinth of footpaths around his home just outside Bristol, a couple of miles from where he was born.

“I’ve been very lucky,” he says. “Making art by walking has given me the freedom to work anywhere in the world. But I’ve come to realise that if I’d been confined, for whatever reason, within a 10-mile radius of Bristol, I could still have achieved everything I’ve wanted to do as an artist.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion